Article

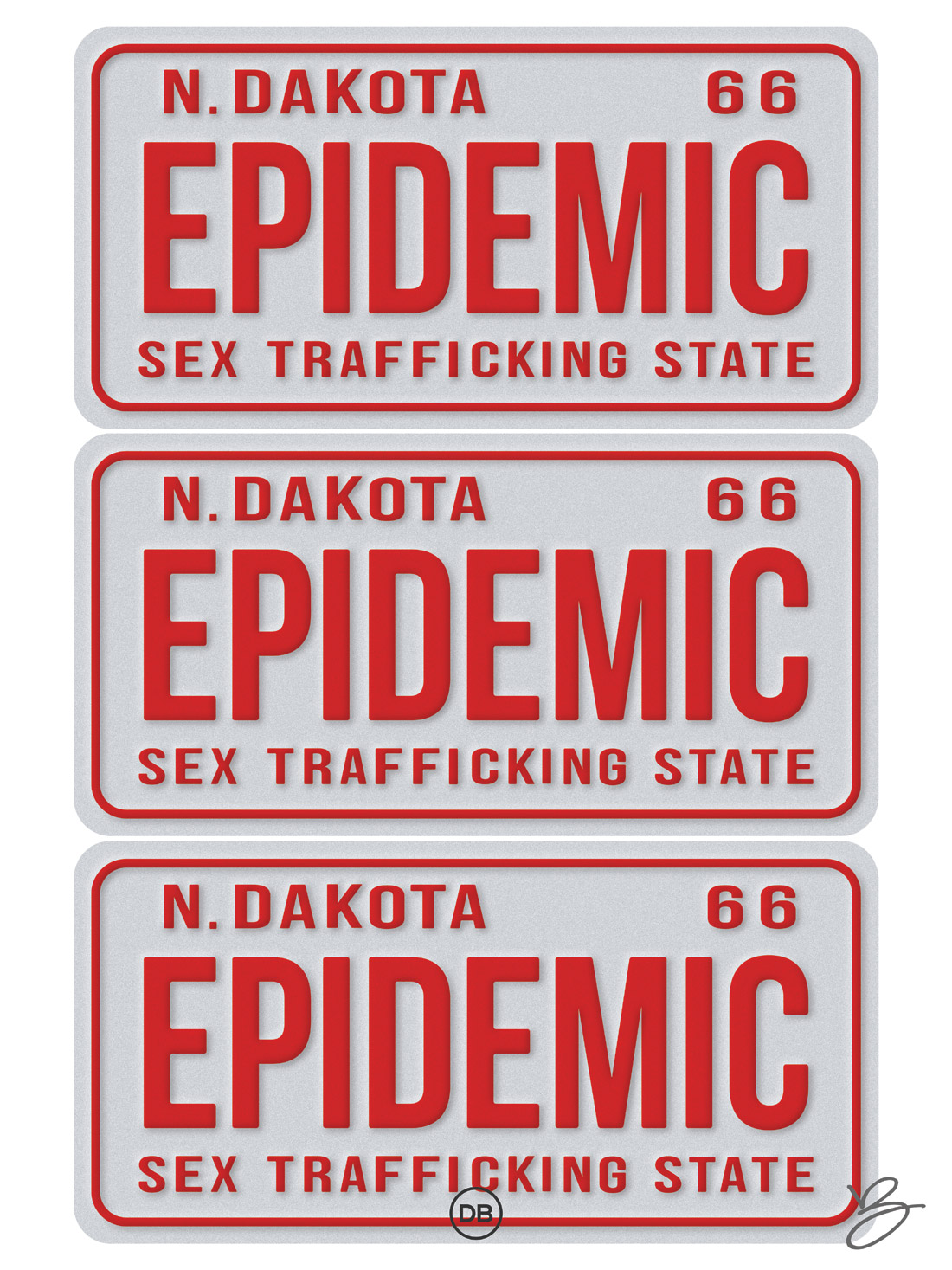

“Six years ago, teenage girls on Fort Berthold, a Native American reservation in North Dakota, started showing up at school with unusual things: manicured nails, fancy makeup, iPods, brand-new cell phones. In a place where the poverty rate is often more than three times the national average and the unemployment rate hovers near 40 percent, no one could figure out how the girls were able to afford such luxuries.

Around the same time, the number of teenage runaways on the reservation, home to the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nations (known collectively as MHA Nation), suddenly spiked. On one weekend alone, Angela Cummings, a former criminal investigator for the tribe, says she could expect to hear from three to 10 sets of parents: “There were a lot of parents searching for children who never came home.” Before long, the girls began cycling through the juvenile justice system for minor offenses like underage drinking. Cummings compared notes with fellow MHA Nation members, and they noticed a trend: Many of the girls had matching tattoos, a red flag for involvement in prostitution, because pimps sometimes brand women that way. “Someone was actually marking these young 13-year-old girls,” says Chalsey Snyder, a former tribal court clerk.

It was disturbing, but there were a lot of strange new things happening on the reservation. North Dakota was in the early days of a massive oil boom in its expansive Bakken shale formation, and tens of thousands of people from out of state were flocking to the area for high-paying oil industry jobs. From its position smack in the middle of the Bakken, Fort Berthold didn’t want to be left out of the action, so MHA Nation leaders started leasing tribal lands held in a common trust to oil companies.

In no time, the number of oil wells on the million-acre reservation swelled to more than 1,000. The wells generate roughly one-third of the state’s total oil output, earning the tribe more than $500 million between 2010 and 2012, accord- ing to a report by the nonprofit Property and Environment Research Center. Roughly two-thirds of that money went to tribe members who hold mineral rights to oil on land they owned on the reservation, the rest to the tribal government. While the system was designed to ensure that earnings would trickle down to adult MHA Nation members, most members, who do not hold mineral rights, have not benefited significantly. (Many members have criticized the tribal government for mismanaging the profits—for example, it purchased a $2.5 million, 149-passenger yacht called Island Girl.)

While the state as a whole was rocked by rapid social change during the boom, the upheaval felt especially chaotic on Fort Berthold. The insular community was swarmed by oil workers—almost all of them men, many young and unattached—who set up camp on their land, went out drinking in their bars, and spent large paychecks gambling at their casino, the 4 Bears Casino and Lodge in New Town, the reservation’s largest city. “[It used to be] on every corner there would be someone you know,” says Sadie Young Bird, who heads the Fort Berthold Coalition Against Violence. “Now, on the corner, it’s a stranger.””

– Marie Claire, Sex Trafficking on the Reservation: One Native American Nation’s Struggle Against the Trade.

Download

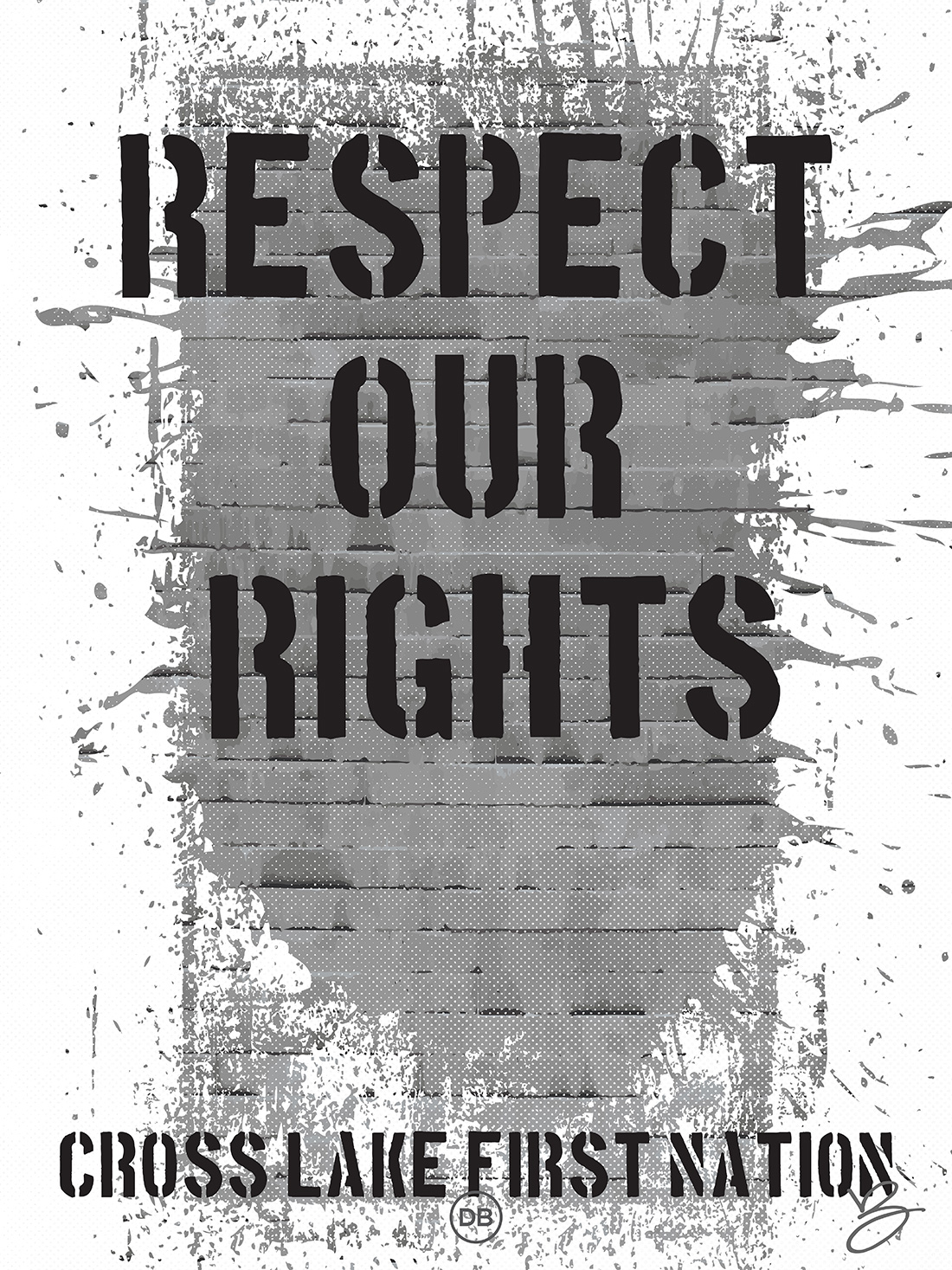

Download the 18″x24″ poster, Indian Country 52 #41 – Sex Trafficking.

Close Ups

Indian Country 52

Indian Country 52 is a weekly project by David Bernie that uses the medium of posters that promote issues and stories in Indian Country.

Creative Commons License

This work by David Bernie is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. You may download, share, and post the images under the condition that the works are attributed to the artist.